B-Movie Bullsh*t

Part Seven

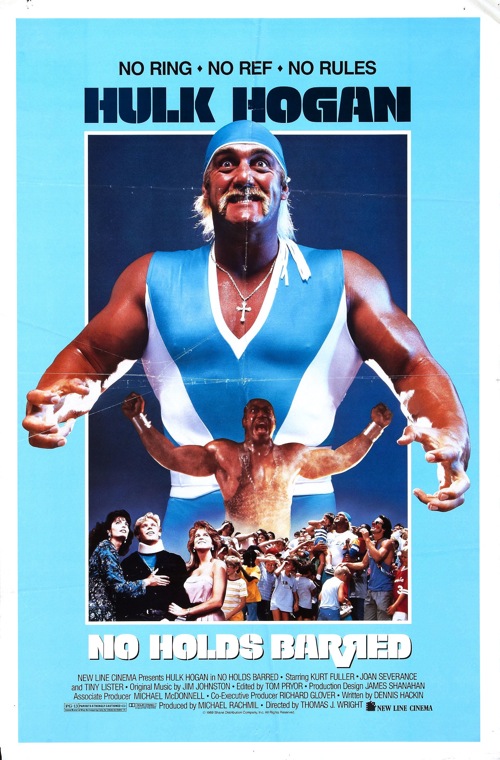

No Holds Barred

(1989)

Synopsis

Rip (no last name given, no last name NEEDED) is the heavyweight champion of the World Wrestling Federation and a thorn in the side of Brell, the sociopathic network president of WTN. Unable to convince Rip to jump to his channel through bribery or violence, Brell decides to make a star out of Zeus, a demented ex-con behemoth who quickly becomes a national sensation fighting in anything goes “No Holds Barred” matches. Rip succumbs to Zeus’ taunts for a match when he cripples Rip’s beloved younger brother, Randy. The night of the big match, Brell kidnap’s Rip’s girlfriend, Samantha, and orders him to give Zeus a good ten minutes before throwing the match. For a time it seems like Rip won’t have to throw anything, but when he sees that Samantha is safe, he finds the inner-strength he needs to defeat his opponent and ensure that Brell never hurts anyone else ever again.

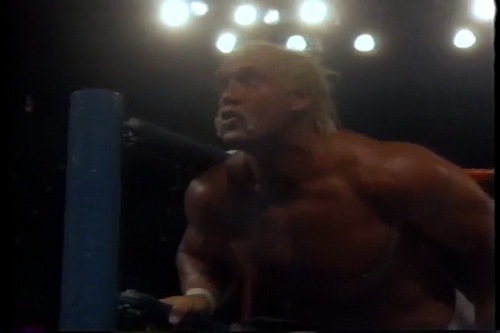

Like most children of the 80s, I fully embraced the lovably theatrical world of professional wrestling. With their inhuman bodies and high-flying acrobatics, professional wrestlers were the closest we ever got to watching real live superheroes in action. The best matches had a beauty, drama and grace to them that was as compelling as any movie you could name. I can still feel the pure joy I experienced when Ricky “The Dragon” Steamboat finally pinned Randy “Macho Man” Savage during Wrestlemania III, after the most tense and excruciating 15-20 minutes of my life. Even though I first saw it on videotape months after it actually happened, I clapped and cheered so loudly I’m sure Steamboat must have heard me wherever he was in the world at the time.

But despite the enjoyment I derived from wrestling, I can honestly say that I never really understood the phenomena of Hulkamania. Even at a very young age I appreciated the fact that the “professional” part of “professional wrestling” was pretty much synonymous with “bullshit” and therefore enjoyed watching the wrestlers who I thought told the best stories in the ring and made it seem almost-kinda legitimate. For all of his enormous popularity, Hulk Hogan was clearly not one of these wrestlers. While many of my peers marveled at the size of his “pythons” I couldn’t help but notice how slow he was, how few moves he seemed to have and how predictably tedious it was whenever he came back from the brink of defeat by feeding on the cheers of the crowd.

But despite the enjoyment I derived from wrestling, I can honestly say that I never really understood the phenomena of Hulkamania. Even at a very young age I appreciated the fact that the “professional” part of “professional wrestling” was pretty much synonymous with “bullshit” and therefore enjoyed watching the wrestlers who I thought told the best stories in the ring and made it seem almost-kinda legitimate. For all of his enormous popularity, Hulk Hogan was clearly not one of these wrestlers. While many of my peers marveled at the size of his “pythons” I couldn’t help but notice how slow he was, how few moves he seemed to have and how predictably tedious it was whenever he came back from the brink of defeat by feeding on the cheers of the crowd.

It didn’t hurt that as the smallest boy in each and every one of my classes, I was naturally inclined to be suspicious of those whose only claim to fame was that they were bigger and stronger than everyone else was. Hulk Hogan clearly benefited from the phenomenon that causes most young kids to assume a nickel is worth more than a dime, because it seems ridiculous that the smaller coin could ever be the more valuable of the two. I, however, knew bigger did not mean better and therefore had little time for those wrestlers who brought nothing else but bulk to the table (although that didn't stop me from loudly cheering for Andre the Giant that same night I cheered for Ricky Steamboat).

I’d like to say that by 13 I had grown too old for all of this, but that would be a ginormous lie. I was still a faithful fan when the Hulkster’s leading man debut was released to theaters (hell, I even occasionally bought the fucking magazine), but my disdain for him kept me from seeing it. If they had released a movie starring Randy Savage, Jake Roberts or (most especially) Miss Elizabeth, I would have probably been there opening day, but I had no time for No Holds Barred, especially since even at that age I could tell that there was no way it could be anything but awful.

I’d like to say that by 13 I had grown too old for all of this, but that would be a ginormous lie. I was still a faithful fan when the Hulkster’s leading man debut was released to theaters (hell, I even occasionally bought the fucking magazine), but my disdain for him kept me from seeing it. If they had released a movie starring Randy Savage, Jake Roberts or (most especially) Miss Elizabeth, I would have probably been there opening day, but I had no time for No Holds Barred, especially since even at that age I could tell that there was no way it could be anything but awful.

Twenty-two years later and my relationship with pro-wrestling is now exactly like the one I have with hardcore pornography—I find the actual product to be mind-numbingly tedious, but the industry itself endlessly fascinating. I can’t get through more than five minutes of any episode of Raw, Smackdown or Impact, but I still enjoy reading the behind the scenes stories about the men and women who made wrestling famous and those who continue on the tradition today.

For this reason I decided it was time to check out Hogan’s famous folly, a film supposedly so terrible that it somehow tarnishes the filmography of the man who starred in Mr. Nanny, Santa With Muscles and Three Ninjas III. Before I even pressed play on my AppleTV remote, I knew I was in for some serious pain, but I never would have dreamed what I would feel when it was over and the end credits began to roll.

Admiration.

Now before you assume I’m writing this while trying to fatally overdose on crazy pills, please understand that I never for once thought that No Holds Barred was a good movie, but instead that I quickly realized that what I was watching wasn’t terrible as a result of filmmaking incompetence, but instead the result of a phenomena I myself know only too well.

There were two groups of people on the set of this film when it was made. The first group consisted of Hogan, producer Vince McMahon and—I’m guessing—leading lady Joan Severance. They believed they were making a real movie—one that would entertain and excite a large mainstream audience. The second group consisted of everyone else who worked on the picture, including director Thomas J. Wright, (the unfortunately named) screenwriter Dennis Hackin, and—especially—co-star Kurt Fuller, who played the part of Rip’s evil network president antagonist.

The folks in the second group did not share the first group’s delusions of grandeur. They knew full well that they were trapped in the middle of a ridiculous vanity project that had no hope of being anything approaching good, so they all said a collective “Fuck it!” and decided that if it was going to fail, it might as well fail on their own spectacular terms.

I came to this conclusion when I finally realized why the film felt so familiar. There was something about its tone that felt so oddly recognizable. It was only a few minutes after Hogan’s character so completely terrified a potential kidnapper that he literally shit his pants that I realized I was watching the greatest film Lloyd Kaufman never made.

As the co-owner of Troma Studios, Kaufman is responsible for such films as The Toxic Avenger, Sgt. Kabukiman NYPD, Tromeo & Juliet, Terror Firmer and Poultrygeist. His films are (in)famous for reveling in bad taste, but in such a way that feels deliberate and—almost—artful. There’s a rebellious quality to his nudity, violence and scatological jokes—each film serving as a cinematic middle finger to what he sees as mainstream Hollywood’s embrace of mediocrity in favor of originality. “You want terrible?” he asks. “I’ll fucking give you terrible.”

As bizarre as it may sound, I finished watching No Holds Barred convinced that it was made with this same attitude in mind. And I completely understood why.

I’ve written before that few, if any, artists, whatever their medium, take on a project expecting it to fail, but it doesn’t take long for the signposts of failure to become impossible to ignore. And once you’ve seen enough of them, you have two choices—succumb or rebel. Succumbing means biting a bullet and creating something that you know is shitty and nothing else; rebelling means becoming subversive and creating something that’s still shitty, but on your own terms and not in the way the people paying your paychecks expected.

I’ve written before that few, if any, artists, whatever their medium, take on a project expecting it to fail, but it doesn’t take long for the signposts of failure to become impossible to ignore. And once you’ve seen enough of them, you have two choices—succumb or rebel. Succumbing means biting a bullet and creating something that you know is shitty and nothing else; rebelling means becoming subversive and creating something that’s still shitty, but on your own terms and not in the way the people paying your paychecks expected.

Whether it’s an artist who plants a subliminal penis in a Disney movie poster or an author who writes a ghost story called “A Boy and His Instrument” in a book called Haunted Schools that’s all about masturbation if you read it correctly (hey, that was me!), these acts of rebellion often go unnoticed by even the most perceptive of audience members, who simply assume that the artists lacked talent and nothing more. But we brave few who have been in these situations ourselves know deliberate, subversive shittyness when we see it and have no choice but to salute and admire it when we do.

It definitely helps my case that the film bears little relation to those found in Group Two’s various filmographies. Although Wright only got the chance to direct one other feature, he’s still managed to amass an admirable amount of credits directing some of the best (The X-Files, Angel and Firefly) and most popular (C.S.I. and N.C.I.S.) episodic shows found on television. Hackin began his career with the critically acclaimed Clint Eastwood comedy Bronco Billy and Fuller remains one of the funniest character actors working today (his crowning achievement being his role in The Tick, where he played Destroyo, a genocidal supervillain whose hatred for mankind derived from the cruel taunts of “Dance, Fatboy, dance!” he received when he was an overweight ballet prodigy. I still quote the line he delivers to Liz Vassey’s Captain Liberty—“You’re not needy, you’re wanty. There’s a difference!”—whenever I can get away with it).

It definitely helps my case that the film bears little relation to those found in Group Two’s various filmographies. Although Wright only got the chance to direct one other feature, he’s still managed to amass an admirable amount of credits directing some of the best (The X-Files, Angel and Firefly) and most popular (C.S.I. and N.C.I.S.) episodic shows found on television. Hackin began his career with the critically acclaimed Clint Eastwood comedy Bronco Billy and Fuller remains one of the funniest character actors working today (his crowning achievement being his role in The Tick, where he played Destroyo, a genocidal supervillain whose hatred for mankind derived from the cruel taunts of “Dance, Fatboy, dance!” he received when he was an overweight ballet prodigy. I still quote the line he delivers to Liz Vassey’s Captain Liberty—“You’re not needy, you’re wanty. There’s a difference!”—whenever I can get away with it).

This is not your standard collection of deluded, untalented assholes. These are skilled professionals who found themselves caught in an absurd situation and decided to not go gently into that good night in order to deal with it.

The question then is how did Group Two manage to make a movie that was deliberately and subversively hilarious without Group One noticing?

To answer this, I’m going to go back to the connection I made between wrestling and hardcore pornography a few paragraphs back by looking at two films that were doomed in their conception due to the inability of their directors to appreciate how much their perspectives had been shifted by their previous work.

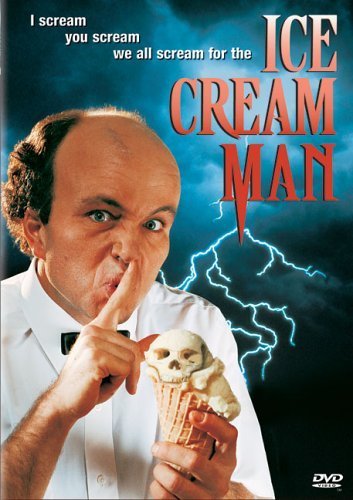

Starring Clint Howard as the serial killing title character, 1995s Ice Cream Man sets itself apart by being a violent, r-rated, nudity-filled slasher movie whose reliance on pre-pubescent protagonists makes it feel like the most socially irresponsible kids movie of all time. Too violent and profane for its target audience and too juvenile for adults, it was a film that could have only been made by someone whose sense of what was and was not appropriate had been lost a long time ago.

Starring Clint Howard as the serial killing title character, 1995s Ice Cream Man sets itself apart by being a violent, r-rated, nudity-filled slasher movie whose reliance on pre-pubescent protagonists makes it feel like the most socially irresponsible kids movie of all time. Too violent and profane for its target audience and too juvenile for adults, it was a film that could have only been made by someone whose sense of what was and was not appropriate had been lost a long time ago.

Norman Apstein was just such a someone. Before making Ice Cream Man, he had—as Paul Norman—directed over 120 hardcore adult movies, including Edward Penishands (in which Tim Burton’s famed romantic hero was reimagined as dude with penises where his hands should be) and Cyrano (in which Edmond Rostand’s famed romantic hero was reimagined as a dude with a penis where his nose should be--sense a theme here?).

Having spent so much of his life focusing his frame on the most intimate of human acts (and putting penises where other body parts should be), Apstein had lost all sense of what did and did not work in the context of a mainstream film.

The same thing happened to Shaun Costello, another hardcore filmmaker, who in 1977 attempted to break into the mainstream big time with Water Power. Intended to be a gritty crime drama, Costello crucially misunderstand the limits of mainstream tolerance by making his villain an obsessed rapist who kidnaps women in order to give them enemas, which Costello showed in close-up pornographic detail. Rather than be hailed as a breakthrough in crime cinema, it was retitled The Enema Bandit and played in exactly the kind of grindhouse porn houses Costello wanted to break away from.

In the case of No Holds Barred, I believe the members of Group One were too immersed in the world of professional wrestling to see how inappropriately it translated into the medium of long-form narrative filmmaking.

Anyone who has spent more than 10 minutes watching anything the WWF produced in the 80s, can appreciate how Hogan and McMahon would have developed this blind spot. They worked on a spectacle designed to appeal to the folks in the cheap seats, who did not demand—and thus were not given—anything approaching subtlety. Pro-wrestling during the Reagan era was a time of black & white and good & evil. The babyfaces were brave, virtuous men who said their prayers, ate their vitamins and loved America, while the heels were capricious cowards who lied and cheated and—worst of all—saluted the communist flag.

Anyone who has spent more than 10 minutes watching anything the WWF produced in the 80s, can appreciate how Hogan and McMahon would have developed this blind spot. They worked on a spectacle designed to appeal to the folks in the cheap seats, who did not demand—and thus were not given—anything approaching subtlety. Pro-wrestling during the Reagan era was a time of black & white and good & evil. The babyfaces were brave, virtuous men who said their prayers, ate their vitamins and loved America, while the heels were capricious cowards who lied and cheated and—worst of all—saluted the communist flag.

You can only produce this kind of entertainment for so long before you either a) buy into it wholeheartedly or b) become so innately cynical that you lose all sense of perspective of what is and is not appropriate. I can’t say for sure which applied to Hogan or McMahon, but if I had to guess it was probably a combination of both.

The reason why people my age loved the WWF in the 80s was because it was squarely aimed at 10 year-old audiences at the exact moment when we were 10 years old. This was a departure from previous decades, where wrestling was considered a largely adult entertainment—boxing with a bit more flair and drama. Yet this change in direction did not drive adults away. If anything wrestling reached its highest peak of mass popularity during this period (Hogan forever supplanting Gorgeous George in the public’s consciousness).

You could be generous and say that the WWF’s 80s product reflected the innocence and simplicity of the era, or you could say that it was adored by morons who wouldn’t know quality entertainment if it set its testicles directly upon their faces (Tea Party reference totally intended). To be fair the exact same thing could be said about the majority of low-budget action movies produced during that time (see, for example, Invasion U.S.A.). I think in order to successfully produce this kind of product you really have to believe in it and disdain it at the same time.

While it is popular for artists to suggest that they are no different than the audiences they work so hard to entertain, I think most know in their hearts that this is bullshit. The difference between creating and consuming product is that the creator has no choice but to be aware of everything that goes into the process required to make the art happen. At the time No Holds Barred was produced the wrestling industry still practiced the tradition of kayfabe—keeping up the pretense of wrestling’s reality into everyday life so as not to betray its essential artifice. That’s why the industry’s slang word for fans was the exact same one con men use for their victims—mark, a term synonymous with “sucker”.

While it is popular for artists to suggest that they are no different than the audiences they work so hard to entertain, I think most know in their hearts that this is bullshit. The difference between creating and consuming product is that the creator has no choice but to be aware of everything that goes into the process required to make the art happen. At the time No Holds Barred was produced the wrestling industry still practiced the tradition of kayfabe—keeping up the pretense of wrestling’s reality into everyday life so as not to betray its essential artifice. That’s why the industry’s slang word for fans was the exact same one con men use for their victims—mark, a term synonymous with “sucker”.

(Kayfabe, more than anything else, is the most fascinating part of wrestling’s history. Imagine if Laurence Olivier had to pretend he was a Danish prince every time he went to a town and played Hamlet. Or if Joan Collins and Linda Evans had to catfight in a water fountain whenever they were spotted somewhere off the set of Dynasty. The only real Hollywood equivalent would be all of the gay and lesbian performers who have pretended to be happily married heterosexuals over the years.)

McMahon and Hogan clearly made a film they thought the “marks” would love, demanding that it be filled with the same black and white moral dramatics that made them so rich to begin with. Hogan’s “Rip” character had to be virtuous to the point of audacity—proclaiming that he was far more interested in charity than self-promotion, gentlemanly setting up a privacy curtain when circumstances force him to share a one-bedroom hotel room with one of the most gorgeous women in the universe, and heroically spending all of his time rehabilitating his injured brother instead of training for the most dangerous match of his life.

McMahon and Hogan clearly made a film they thought the “marks” would love, demanding that it be filled with the same black and white moral dramatics that made them so rich to begin with. Hogan’s “Rip” character had to be virtuous to the point of audacity—proclaiming that he was far more interested in charity than self-promotion, gentlemanly setting up a privacy curtain when circumstances force him to share a one-bedroom hotel room with one of the most gorgeous women in the universe, and heroically spending all of his time rehabilitating his injured brother instead of training for the most dangerous match of his life.

At the same time his opponents are as venal and mindlessly evil as any ever seen onscreen. Made just a year after Ted Turner bought Atlanta’s NWA promotion with the intention of turning it into the nationally televised WCW (and thus become the first non-regional competition that the WWF faced in years), it doesn’t seem like an accident that the main villain is a network president with the moral compass of a dung beetle. That said, Brell bears no signs of Turner’s distinctive manner or personality. I’d say this was to avoid a potential libel suit, but I remember a few years after No Holds Barred was released McMahon aired a series of skits featuring a Turner clone behaving like a redneck buffoon, so it’s not like he wasn’t afraid to go there.

Even more hilarious is Zeus, who plays the same role Clubber Lang and Ivan Drago did in Rocky III & IV, but without any of their depth, subtlety or nuance. Tommy (“Tiny” to his friends) Lister’s performance is so perversely over the top that it takes on a kind of absurdist genius. With his crossed eyes, tatooed head, and penchant for uncomfortable metallic clothing, he actually seems too over the top even for wrestling, which turned out to be true when the character was unsuccessfully transplanted into the real WWF to promote the movie (it didn’t help that Lister had no professional wrestling experience and managed to be even clumsier in the ring than Hogan). Amazingly, out of all the performers in the film, he’s probably had the most consistently successful career, having not only worked non-stop since his appearance in No Holds Barred, but also making his mark in high-profile productions like The Fifth Element, Jackie Brown and The Dark Knight.

That said, the bad guys are at least given the chance to develop actual onscreen presences, which cannot also be said for Rip’s friends. The brother who inspires him to win all of his matches is just a handsome blond guy with a goofy 80s haircut (who would, funnily enough, go on to become Jacob, Lost’s mysterious protector of the golden spring). His trainer is just an old black dude and at least two of the other people who hang with him are never even introduced onscreen.

The film’s only other character with a personality is Sam (short for Samantha, which just boggles Rip’s mind), Rip’s new business manager who has to work harder at her job than a man would because she looks just like Joan Severance and everyone within a hundred mile radius wants to have crazy-hot-monkey-sex with her. There’s no doubt that Severance is astonishingly attractive, but in such a way that detracts rather than adds to her credibility. She’s one of those actresses who is simply too good-looking, since it becomes impossible to imagine her in any other role than that of model or actress. It doesn’t help that she’s precisely the kind of limited performer required to make sure that Hogan doesn’t get wiped off the screen.

The film’s only other character with a personality is Sam (short for Samantha, which just boggles Rip’s mind), Rip’s new business manager who has to work harder at her job than a man would because she looks just like Joan Severance and everyone within a hundred mile radius wants to have crazy-hot-monkey-sex with her. There’s no doubt that Severance is astonishingly attractive, but in such a way that detracts rather than adds to her credibility. She’s one of those actresses who is simply too good-looking, since it becomes impossible to imagine her in any other role than that of model or actress. It doesn’t help that she’s precisely the kind of limited performer required to make sure that Hogan doesn’t get wiped off the screen.

As I’ve already said, there are two films at play here, although sometimes the lines do seem to cross. The film’s bizarre penchant for scatological or inappropriately sexual jokes(turns out the bed’s noisily jiggling is the result of Rip exercising, not furiously masturbating) has a direct connection to similar material that has shown up on McMahon’s wrestling shows over the years, but at the same time they are taken to such perversely extreme levels that they extend beyond the realms of mere bad taste to that of deliberate transgression.

This is most evident in the moments Hogan and McMahon obviously did not intend to be funny. I’ve complained in the past of films that were so badly made that they transformed into inadvertent self-parody, but in the case of No Holds Barred I am certain this is only half the case. Hogan and Severance are clearly sincere, but everyone else around them is just as clearly cognizant of how ridiculous the whole enterprise is and they show it.

This is most evident in the moments Hogan and McMahon obviously did not intend to be funny. I’ve complained in the past of films that were so badly made that they transformed into inadvertent self-parody, but in the case of No Holds Barred I am certain this is only half the case. Hogan and Severance are clearly sincere, but everyone else around them is just as clearly cognizant of how ridiculous the whole enterprise is and they show it.

For someone like me the result is fascinating, but for the average wrestling fan for which it was intended it was clearly bewildering. For most people deliberately shitty is still just shitty and a waste of time and money, which explains why the filmmakers’ efforts here went almost completely unnoticed.

I say “almost”, because I know the film has at least one acolyte out there. Back when I was 19, I was in my second year of university (the last that would actually count, as my third and final year was pretty much a write off) and taking a film studies course that examined the auteur theory by looking at the films of Dreyer, Bresson, Fuller and Kurosawa (among others I may have forgotten). Among the students was another young man, whose name has been lost to time. He suffered from Down syndrome and was there as part of a program that allowed those with special disabilities to enjoy the university experience. It was a noble idea to be sure, but in practice it meant we all had to listen to his loud snoring after one of the boring foreign films or lectures inevitably put him to sleep.

Near the end of the year, he finally lost his patience during a lecture and threw up his hand. Professor Beard (who would go on to write The Artist as Monster, an excellent analysis of the films of David Cronenberg) asked him what his question was and it became clear that he had spent all of this time in class waiting for the subject of his favourite film to finally be discussed and he could no longer wait for this to happen organically.

With the floor now his he proceeded to describe in detail the climatic match between Rip and Zeus. Everyone listened patiently and it was only when it became painfully clear that he wasn’t about to stop that Professor Beard interrupted him and explained that he couldn’t answer the “question” because he hadn’t seen the film.

In retrospect, I wish he had. I would have vastly preferred to debate the symbolism of Rip’s “Rip ‘Em” T-Shirt than hear another word about Diary of a Country Priest ever again.

Of course, the greatest irony of the film is that five years after the failure of No Holds Barred, Hogan did what Rip would not and jumped over to Turner's WCW following the promise of a bigger paycheck. As the innocence of the 80s turned into the cynicism of the 90s, Hogan eventually abandoned his babyface image and became Hollywood Hogan, the leader of the renegade N.W.O. He would eventually return to McMahon's company, but by that point he was purely a nostalgia act. Though he would gain fame as a reality tv star, his film debut clearly represented his jump the shark moment. No Holds Barred was supposed to be proof that he was more than a mountain of muscle, but it ended up being proof that he was little else. The lesson being that it's better to be the biggest of all fish in a disrespected pond than the asshole who's crying while everyone else is trying not to laugh out loud.