In a past post I described (at length) the reasons behind my firmly held belief that the IMDb is the most depressing website to be found on the internet, in so far as it serves as a cold and disheartening record of thousands of broken dreams. But despite this harsh fact, I often find myself lost in its virtual pages, inevitably enjoying some new and exciting discovery in each filmography I come across, no matter how obscure their subject may be. The sensation is identical to the feeling I had as a kid reading those thick Leonard Maltin Movie Guides from cover to cover as if they were the most absorbing novels ever written. With each new name and title I find another opportunity to increase my appreciation of the art, which I am grateful for after 20+ years of cinematic study. Thanks to the IMDb I have unearthed many treasures that might have remained buried had I not first found out about them within its online pages.

In a past post I described (at length) the reasons behind my firmly held belief that the IMDb is the most depressing website to be found on the internet, in so far as it serves as a cold and disheartening record of thousands of broken dreams. But despite this harsh fact, I often find myself lost in its virtual pages, inevitably enjoying some new and exciting discovery in each filmography I come across, no matter how obscure their subject may be. The sensation is identical to the feeling I had as a kid reading those thick Leonard Maltin Movie Guides from cover to cover as if they were the most absorbing novels ever written. With each new name and title I find another opportunity to increase my appreciation of the art, which I am grateful for after 20+ years of cinematic study. Thanks to the IMDb I have unearthed many treasures that might have remained buried had I not first found out about them within its online pages.

But this alone is not the only reason why I cannot stay away from the site for more than a few days (or hours) at a time. The other reason, though, is directly tied into the aspect of the site that accounts for its melancholy aftertaste. The more pages you read, the more often you find yourself confronted by the title at the top of each of its subjects’ resumes. Depending on who that subject is this first title could merely be the most recent of their projects and will soon find itself buried under future endeavors, but more often than not this first entry serves as a monument to the end of a person’s film and television career. Beside that title is a date and with that date you can measure the length of time that passed since its subject ceased to be an actor/director/writer/producer/whatever and went on to live as a real, ordinary, average, not-at-all-special human being.

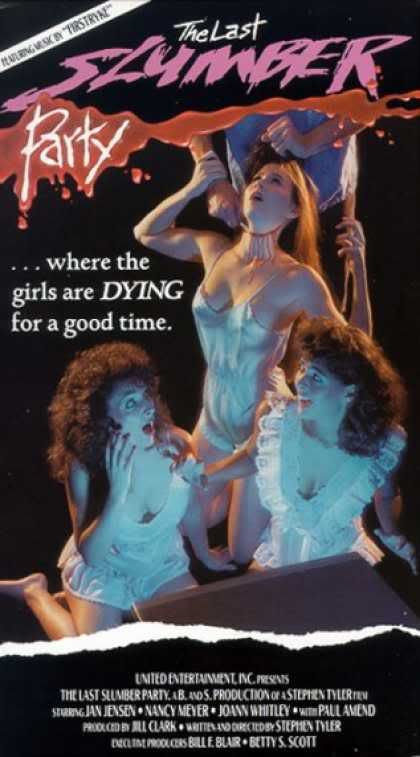

It’s this undocumented period of time that fascinates me more than I can describe. What has this person done in the 20 years that passed since the two-line bit part on Night Court that ended their career? Have they accomplished anything? Are they happy? Filled with regret? Does anyone in their current lives know or appreciate who they once were? Do they want them to? These last two questions are especially intriguing when you look over the pages of people who were involved in the less respectable areas of the industry. One has to wonder, for example, if anyone involved with The Last Slumber Party is apt to mention their participation in that monstrosity at every available opportunity or if they (much more wisely) live in constant fear that someone they know might stumble upon the film and discover their deep, dark, terrible secret. In the past, keeping such a skeleton hidden in your closet might not have been difficult, but in the age of Google all of our skeletons are becoming a lot harder to hide.

These last two questions are especially intriguing when you look over the pages of people who were involved in the less respectable areas of the industry. One has to wonder, for example, if anyone involved with The Last Slumber Party is apt to mention their participation in that monstrosity at every available opportunity or if they (much more wisely) live in constant fear that someone they know might stumble upon the film and discover their deep, dark, terrible secret. In the past, keeping such a skeleton hidden in your closet might not have been difficult, but in the age of Google all of our skeletons are becoming a lot harder to hide.

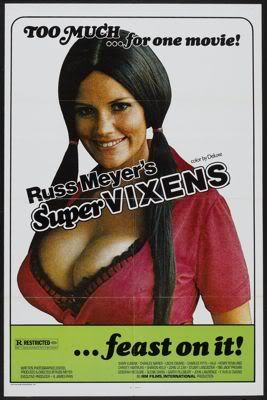

I write this because I just spent a somewhat ambivalent 90 minutes watching a long-forgotten mid-70s curiosity entitled Chesty Anderson USN. For fans of such cinema, its significant only as the second—and last—film of beloved Russ Meyer discovery, Shari Eubank, whose dual role in SuperVixens instantly earned her a kind of b-movie immortality that can be considered either a blessing or a curse depending on the feelings of the individual it’s imposed upon. While Meyer’s best film remains Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (despite what some fans of Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! may foolishly claim), a lot of the credit for its success can be given to his screenwriter Roger Ebert (yes, that Roger Ebert) and especially—in my opinion—the film’s composer Stu Phillips (whose songs are likely to remain with you longer than the any of film’s colourful images). SuperVixens, on the other hand, is pure unfiltered Meyer (its final opening credit reads “Written, Photographed, Edited, Produced and Directed by RUSS MEYER”) and for that reason has always struck me as his most important film—the one for which his reputation as a genuine softcore auteur became wholly deserved.

While Meyer’s best film remains Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (despite what some fans of Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! may foolishly claim), a lot of the credit for its success can be given to his screenwriter Roger Ebert (yes, that Roger Ebert) and especially—in my opinion—the film’s composer Stu Phillips (whose songs are likely to remain with you longer than the any of film’s colourful images). SuperVixens, on the other hand, is pure unfiltered Meyer (its final opening credit reads “Written, Photographed, Edited, Produced and Directed by RUSS MEYER”) and for that reason has always struck me as his most important film—the one for which his reputation as a genuine softcore auteur became wholly deserved.

Driven by a cartoonish energy perfectly matched by the comic book bodies of its heroines, SuperVixens flirts with self-parody but manages to remain true to itself, unlike his subsequent efforts Up!, Beneath the Valley of the UltraVixens and the released-even-though-it-was-obviously-never-finished-and-wouldn’t-have-made-sense-even-if-it-had-been Pandora Peaks (a project whose failure can be excused by the Alzheimer’s that was slowly wrecking Meyer's mind as he very-slowly worked on it) all of which seem desperate and uninspired in comparison.

That said, there’s another reason SuperVixens satisfies more than most of Meyer’s other films. According to Jimmy McDonough’s biography of the director Meyer was introduced to a 28 year-old dancer named Shari Eubank by his friend and occasional star Haji, who had worked with her at a club called The Classic Cat and later said, “She was a damn good actress and she didn’t even know it.” Meyer was instantly smitten and for good reason. Not only did she have the kind of figure that had made his films famous, but unlike his previous and future discoveries such as Tura Satana, Erica Gavin, Raven De La Croix and Kitten Natividad, Eubank exuded a classic wholesomeness almost completely absent from his oeuvre. For this reason it seems strange that Meyer originally hired her to play the part of SuperAngel—the film’s representation of female power at its worst—and gave the part of Angel’s virtuous opposite, SuperVixen, to his then-wife Edy Williams--quite possibly the least wholesome actress of the era.

That said, there’s another reason SuperVixens satisfies more than most of Meyer’s other films. According to Jimmy McDonough’s biography of the director Meyer was introduced to a 28 year-old dancer named Shari Eubank by his friend and occasional star Haji, who had worked with her at a club called The Classic Cat and later said, “She was a damn good actress and she didn’t even know it.” Meyer was instantly smitten and for good reason. Not only did she have the kind of figure that had made his films famous, but unlike his previous and future discoveries such as Tura Satana, Erica Gavin, Raven De La Croix and Kitten Natividad, Eubank exuded a classic wholesomeness almost completely absent from his oeuvre. For this reason it seems strange that Meyer originally hired her to play the part of SuperAngel—the film’s representation of female power at its worst—and gave the part of Angel’s virtuous opposite, SuperVixen, to his then-wife Edy Williams--quite possibly the least wholesome actress of the era.

But then Williams decided she wanted to be recognized as a serious actress and would no longer appear naked on film (a career choice she would reverse a few years later when it became abundantly evident no one would hire her for any other reason). Unable to find a suitable replacement, he decided Eubank could play both roles—a choice made out of desperation that accidentally gave the film a bit of unintended thematic depth and which also made the character infinitely more sympathetic.

For a neophyte actress, Eubank proved remarkably adept in both roles. If her SuperAngel sometimes seems a bit over-the-top, it’s always to the film’s benefit and perfectly in keeping with Meyer’s manic style. As a character, SuperAngel is a broadly drawn representation of the worst kind of woman—supremely narcissistic, lazy, unsupportive, selfish and jealous—yet Eubank is able to show how she gets away with it with a single innocent look (it doesn’t hurt that the look just happens to be perched on top of that body).

In a weird way, casting Eubank as SuperAngel works against the film in that when she finally pushes a man too far, her violent comeuppance lacks the sense of justice Meyer pretty obviously wanted to convey. Many commentators have expressed offense over the scene where policeman Harry Sledge (Meyer regular and well-known character actor Charles Napier) is driven to kill her after she cruelly mocks his inability to get an erection in her presence (“Not ready? With my beautiful body? You got a lot of nerve buster telling me you’re not ready!”), and while the scene is wildly over the top and does border on the wrong side of misogynistic, I believe this has a lot to do with the fact that even though SuperAngel the character isn’t sympathetic, Shari Eubank the actress is, and it’s painful to see her suffer in such a violent way. Such is her presence in the film, the thought of her no longer being in it feels like a violation and it was only through happenstance that this potential mistake managed to be corrected. Had Edy Williams been willing to take her clothes off for her husband, SuperVixens would have ended being a very different (and most likely unsatisfying) film.

Unlike SuperAngel, the role of SuperVixen didn’t require as much effort from the actress. “Vix” (“As [her] friends call [her]”) is a sweet, hard-working young widow whose gas station/diner is literally an Oasis for Curt Ramsey, the film’s hapless and harried male protagonist. Though their onscreen courtship isn’t given much screen time and basically consists of the two of them cavorting nakedly in the wild, their relationship is easily the sweetest and most romantic in all of Meyer’s films—a fact due as much to the performers as any effort from the director.

It’s unfair, however, to suggest that Eubank’s success in the film is based entirely on her own charisma. Meyer’s contribution to her iconic performance is made evident by even a single viewing of the only other film she appeared in, the above-mentioned Chesty Anderson USN, in which she flounders under the weight of a poorly-written role in a badly-directed movie. For those of you who look to titles as a way to judge whether or not a film is right for you let the example of Chesty Anderson USN serve as fair warning of your folly.

It’s unfair, however, to suggest that Eubank’s success in the film is based entirely on her own charisma. Meyer’s contribution to her iconic performance is made evident by even a single viewing of the only other film she appeared in, the above-mentioned Chesty Anderson USN, in which she flounders under the weight of a poorly-written role in a badly-directed movie. For those of you who look to titles as a way to judge whether or not a film is right for you let the example of Chesty Anderson USN serve as fair warning of your folly.

Let’s start with that Chesty part.

“Now,” you must be thinking, “any movie that goes to the trouble of advertising it’s heroine’s pulchritude in the title must surely be a sexy romp filled to the brim with enticing female nudity.”

WRONG!

Despite its featuring a cast Meyer himself would be proud of [joining Eubank are such shapely actresses as Rosanne Katon, Dorrie Thompson, Dyanne “Ilsa” Thorne, Joyce Gibson (aka Joyce Mandel) and—in a wordless cameo as a gangster moll—fellow SuperVixens alum, Uschi Digard], the amount of actual nudity seen in the film clocks in at around 30 seconds. The effect is not dissimilar to casting Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Steven Segal, Jean Claude Van Damme, Charles Bronson, Chuck Norris, Jackie Chan, Vin Diesel, Jet Li, Nicholas Cage and Sean Connery in a remake of 12 Angry Men. As cool as it may seem for the first ten minutes, at a certain point you realize that they’re really just going to talk for the whole movie and a certain galling disappointment quickly begins to set in.

Despite its featuring a cast Meyer himself would be proud of [joining Eubank are such shapely actresses as Rosanne Katon, Dorrie Thompson, Dyanne “Ilsa” Thorne, Joyce Gibson (aka Joyce Mandel) and—in a wordless cameo as a gangster moll—fellow SuperVixens alum, Uschi Digard], the amount of actual nudity seen in the film clocks in at around 30 seconds. The effect is not dissimilar to casting Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis, Steven Segal, Jean Claude Van Damme, Charles Bronson, Chuck Norris, Jackie Chan, Vin Diesel, Jet Li, Nicholas Cage and Sean Connery in a remake of 12 Angry Men. As cool as it may seem for the first ten minutes, at a certain point you realize that they’re really just going to talk for the whole movie and a certain galling disappointment quickly begins to set in.

And I suppose you’re now thinking, “Okay, so there ain’t much sex. At least the USN tells us we’re about to see a fun service comedy in the vein of Buck Privates, Stripes or In the Army Now.”

Though the film’s heroines are portrayed as being WAVES, their service in the military has as much impact on the plot as a butterfly flapping its wings in China does on the overall future of mankind. Had the filmmakers instead found cheap and easy access to an abandoned hospital and a trunk full of old nurse costumes, the film could have been turned into Chesty Anderson RN with literally ten minutes worth of script revision.

But then if Chesty Anderson USN isn’t a sexy military romp, what the hell is it?

I’m not sure I should answer that question, since doing so would require me to spend more time thinking about its plot than the filmmakers ever did. Beyond the criminal lack of nudity, the most frustrating aspect of the film is its shocking lack of urgency. Near the beginning of the film Chesty’s younger sister is kidnapped and killed by the mob to stop her from ruining the career of her old boss, a corrupt, cross-dressing senator, and the subsequent investigation into her disappearance that then dominates the rest of film is given all of the gravitas of a search for a Jackson Five album needed for a sorority party scavenger hunt.

The blame for this rests on the shoulders of director Ed Forsyth who was not only incapable of handling the script’s bizarrely disparate tones, but was also clueless when it came time to direct his cast. As memorable as Eubank was in her first film, here she comes off as lifeless and flat (emotionally if not physically). She never seems that worried about what happened to her sister and shows absolutely no signs of anger or grief when she finally uncovers the truth.

Her male co-stars fare little better. Recognizable character actor Stanley Brock’s performance (seen here with Dyanne Thorne) as the lecherous doctor who orders the WAVES to strip to their waist (which in this case means taking of their shirts, but not their bras) no matter what their complaint would have been embarrassing on a vaudeville stage in 1926, much less in a movie made half a century later.

Scatman Crothers (billed here as Scat-Man) is a long way away from The Shining, but he only appears in one--unnecessary--scene, while the usually brilliant Fred Willard is saddled with the lame heroic boyfriend role and is given zero opportunity to showcase his tremendous comic talents.

The only performers who come off well are Katon (who in 1978 would become Playboy’s Miss September and in that capacity would go on to appear in the third episode of a certain variety show), who manages to take on the sassy black mama role without making her character seem like a tired stereotype, and Marcie Barken , whose turn as the trampy, flat-chested redhead earns the film its only real laughs.

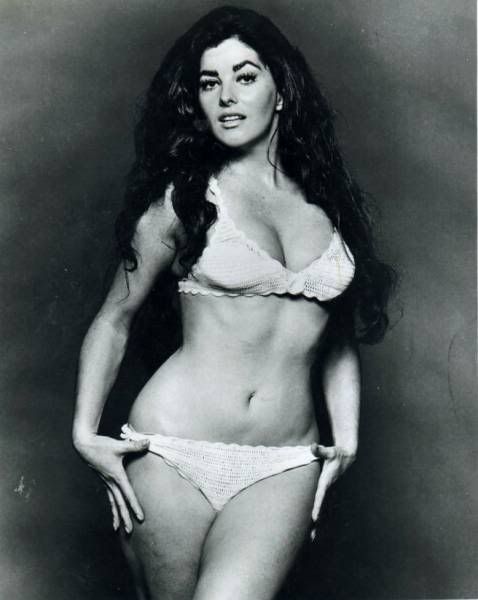

Still, as bad as the film may be it is only a footnote in the brief career of its star. Unlike 99% of the folks whose careers are documented on the IMDb, Shari Eubank earned true cinematic immortality and lives on in the memories of all those who’ve seen her first film.

After Chesty Anderson USN was released in 1976, the 30 year-old actress (who others described as sensitive and naïve), gave up on show business and eventually returned to her hometown of Farmer City, Illinois, where she had once been a cheerleader and the homecoming queen. In the intervening decades it was rumored she’d gotten a degree in Education and taught Drama and English in her hometown’s small school system. Now, thanks to Google and the increasing necessity for all institutions to be online, rumor has become fact. All those fans who want to know what SuperAngel/SuperVixen looks like today, merely have to visit the staff section of the webpage devoted to Farmer City’s Blue Ridge Junior High.

And some may be happy to leave it at that, but I suspect many will be driven to distraction by the questions this raises. Farmer City is a small community, so it’s unlikely her acting career has ever been a secret, but there would have been a period before home video where her appearance in a Russ Meyer film would have only been an unprovable legend among her students:

“Hey, did you hear Ms. Eubank was in a porn movie?!?!”

“No way!”

“It’s true! My dad says he saw it. She was naked and everything!”

“Your dad’s a liar.”

“Is not! Billy’s dad says he saw it too.”

“Really?”

“Uh-huh!”

“What’s it called?”

“I dunno. Something like Wonder Boobs, I think….”

Fast forward a decade later:

“You’ve got to come over to Billy’s place!”

“Why?”

“He just got back from a trip to his cousin’s in Chicago and he brought something back!”

“What?”

“It’s a copy of that porno Ms. Eubank was in!”

“No way!”

“Yeah, his cousin has all of these movies and Billy recognized the title.”

“Has he watched it?”

“Only like a dozen times!”

“She’s really naked in it?”

“Really, really naked!”

Fast forward to today:

“Let’s Google Ms. Eubank.”

“Okay. What’s her first name, again?”

“I think it’s Shari.”

“Okay, here we go.”

“Holy shit! Are those her boobs?”

“I love the internet.”

In all seriousness, it is virtually impossible for anyone with a single wit’s worth of imagination to not wonder how they would have reacted to the knowledge that their junior high school language arts teacher was once the buxom star of one of the best softcore movies ever made. And those of us blessed with even more imagination than that cannot help but go on to ponder what it must have been like to be that junior high school language arts teacher whose interesting former career is inevitably discovered each year by a new crop of hormone-addled students.

And with this being just one untold story hinted at in the IMDb, you can understand why it’s difficult for me to stay away from its depressing online pages for any length of time. The sadness they sometimes make me feel being nothing compared to the wonderful curiosity they inspire.