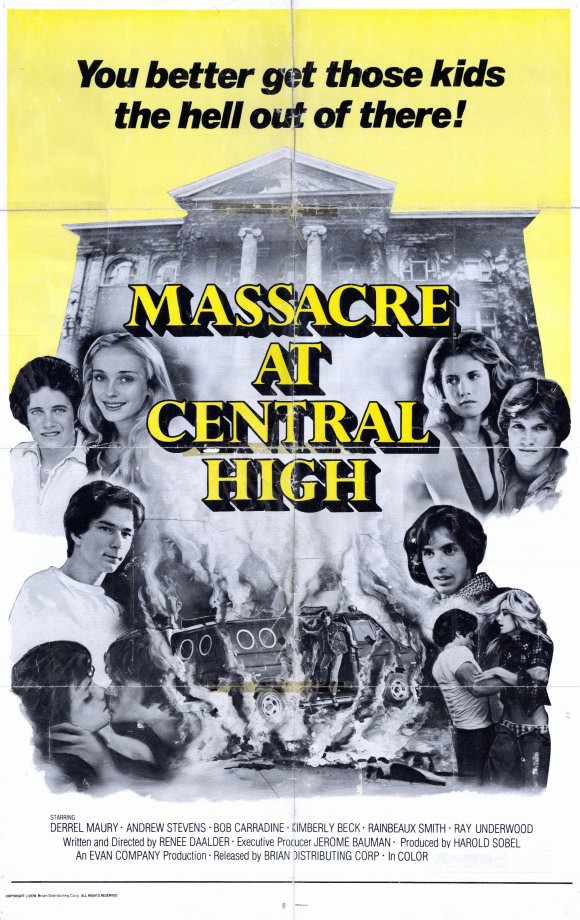

B-MOVIE BULLSH*T - Part Ten "An Allegory With Tits and Explosions"

Saturday, November 12, 2011 at 6:00AM

Saturday, November 12, 2011 at 6:00AM B-Movie Bullsh*t

Part Ten

Massacre at Central High

(1976)

Synopsis

New kid David learns a lot during his first day at Central High. It turns out the small school is run with an iron first by a quartet of rich male students, including his old friend Mark, who just happens to be dating Teresa, the very pretty girl David immediately takes a liking to. Mark tries to get David into the exclusive clique, but David refuses to associate himself with such overt bullies. His impatience reaches its boiling point when he catches them (without Mark) trying to rape two female students. He beats the snot out of them, and—in retaliation—they drop a car on his leg. Once a dedicated runner, David is now left with a permanent limp. He gets his revenge by arranging fatal accidents for his three assailants. At first, the students at Central High enjoy their newfound freedom from the clique’s tyranny, but as that freedom turns to chaos, the various factions try to convince David to help them takeover the school and run it in their image. Realizing he’s merely created more bullies, David begins to systematically murder the new crop of wannabe rulers. With no other way to end this eternal cycle, he decides to blow up the school during the annual Alumni Dance, but when Teresa arrives at the gymnasium and tells him she’s not going to leave, even if it means dying with everyone else, he grabs the bomb and runs outside. It detonates while in his hands, ending the violence once and for all.

Massacre at Central High is a fascinating film. Viewed from every possible angle, it’s an exploitation movie down to its very core. It’s a revenge thriller with creatively planned murders; it has a mega-buttload of impressive explosions; and it features more than its share of gratuitous nudity. Even its title was chosen specifically to capitalize on the popularity of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Yet for all of its exploitative elements, there’s no getting around the fact that writer/director Renee Daalder (Dutch and male) was trying to do something more ambitious than create another drive-in movie.

One of the reasons I prefer writing about low budget genre film is because I take a lot of pleasure out of mining gold out of areas where others insist it cannot exist. To look beyond the surface and imagine what the filmmakers might have been thinking when they agreed to work on another cheap blood and tits movie. I am not so delusional to not accept that most did so only with “Hey! Great! A paycheck!” in their minds, but—based on my own personal experience as a writer—I also know how hard it is to completely bury one’s own personal pretensions in even the most cynical of creative enterprises. I love the “Bullsh*t” artists come up with to justify their artistic degradation, and I considered it my duty to support their delusions with the kind of self-indulgent analysis typically only reserved for more respected, mainstream material.

One of the reasons I prefer writing about low budget genre film is because I take a lot of pleasure out of mining gold out of areas where others insist it cannot exist. To look beyond the surface and imagine what the filmmakers might have been thinking when they agreed to work on another cheap blood and tits movie. I am not so delusional to not accept that most did so only with “Hey! Great! A paycheck!” in their minds, but—based on my own personal experience as a writer—I also know how hard it is to completely bury one’s own personal pretensions in even the most cynical of creative enterprises. I love the “Bullsh*t” artists come up with to justify their artistic degradation, and I considered it my duty to support their delusions with the kind of self-indulgent analysis typically only reserved for more respected, mainstream material.

In the case of Massacre at Central High, though, I don’t have to expend any effort at all to figure out what Daalder was trying to say in his blood and tits drive-in movie. In fact, it would take far more effort to deny the film's pretensions and dismiss it as just another horror movie. In the case of this film, the question isn’t whether or not subtext exists, but whether or not that subtext allows the film to transcend what might otherwise be some pretty fatal flaws.

Based on plot description alone, the film is a revenge thriller with horror movie elements, but when you actually see it, it becomes clear that its genre elements only exist to appease the producers who financed it. In actual fact, Massacre at Central High is an allegorical film—with blood, explosions, and plenty of tits and ass. Made by a filmmaker who grew up in post-war Europe, it’s a film about fascism whose theme is so explicit the characters actually comment on it (but not in an overt, self-referential post-modern way).

Based on plot description alone, the film is a revenge thriller with horror movie elements, but when you actually see it, it becomes clear that its genre elements only exist to appease the producers who financed it. In actual fact, Massacre at Central High is an allegorical film—with blood, explosions, and plenty of tits and ass. Made by a filmmaker who grew up in post-war Europe, it’s a film about fascism whose theme is so explicit the characters actually comment on it (but not in an overt, self-referential post-modern way).

And the thing about allegories is that, as an audience, we allow them more creative leeway than we do more traditional stories. Once we realize that the message of the film is its defining purpose, we become less pre-deposed to judge it as a whole work of art and instead focus on how well it communicates its point.

Because of this, Massacre at Central High gets away with the implausible in ways other less-ambitious genre films couldn’t. We not only accept the tiny student population, the complete absence of adults (until the very last dance sequence), and the unlikely murder scenarios, but actually understand how they work to strengthen the film’s message. What would otherwise be considered budget-related flaws, now seem like deliberate choices made for intelligent reasons.

When I wrote the above synopsis of the film, I actually made several attempts to not give away what it was really about, but—as an allegory—its theme is so directly interwoven into its plot that I couldn’t untangle it. David’s motivation for killing the other students once he’s killed the three who originally hurt him only makes sense in an allegorical context. When Mark confronts him late in the picture, he describes himself as a “psycho madman”, but the film doesn’t abandon him as its protagonist and makes no attempt to condemn him for his actions as he commits them. After he kills himself in order to spare the life of the girl he loves, the film ends with her telling her boyfriend that they’re both going to say he died getting rid of a bomb other (now dead) students hid in the school—making it clear that even in the world of the film only two people will ever know he wasn’t a hero.

When I wrote the above synopsis of the film, I actually made several attempts to not give away what it was really about, but—as an allegory—its theme is so directly interwoven into its plot that I couldn’t untangle it. David’s motivation for killing the other students once he’s killed the three who originally hurt him only makes sense in an allegorical context. When Mark confronts him late in the picture, he describes himself as a “psycho madman”, but the film doesn’t abandon him as its protagonist and makes no attempt to condemn him for his actions as he commits them. After he kills himself in order to spare the life of the girl he loves, the film ends with her telling her boyfriend that they’re both going to say he died getting rid of a bomb other (now dead) students hid in the school—making it clear that even in the world of the film only two people will ever know he wasn’t a hero.

So, then, if the film is an allegory, is it a good one? Does it get its point across? Is it intelligently argued? Or is it overtaken by the cheesy self-importance that often dooms such projects?

For the first three points, my personal feelings range from “I dunno,” to, “Probably not.” For an allegory about fascism, I’m not sure what ultimate point I’m supposed to take away from it. It’s clearly bad, but am I also supposed to conclude that it’s impossible to avoid? Each of the different student factions are obviously drawn to represent parts of modern society, including the wealthy, poor, educated, liberal, and middle-classes. All of them are deemed capable of creating their own forms of tyranny, suggesting that true freedom is impossible, which would mean more if the film didn’t also suggest that true freedom leads to anarchy without someone in charge. Thus David’s decision to blow up the whole school represents a clearly nihilistic worldview in which the only solution is the final solution. Of course, he fails to do this for the most romantic of reasons, but the hopelessness of his decision remains. Are we to then read the film as a treatise against armed revolution? If so, does that mean the film thinks David should have given in like everyone else and let the bullies rule Central High? That doesn’t seem likely, which explains my confusion. The point of an allegory is to have a point, which Massacre at Central High may have, but which is the only aspect of its production left at all ambiguous.

For the first three points, my personal feelings range from “I dunno,” to, “Probably not.” For an allegory about fascism, I’m not sure what ultimate point I’m supposed to take away from it. It’s clearly bad, but am I also supposed to conclude that it’s impossible to avoid? Each of the different student factions are obviously drawn to represent parts of modern society, including the wealthy, poor, educated, liberal, and middle-classes. All of them are deemed capable of creating their own forms of tyranny, suggesting that true freedom is impossible, which would mean more if the film didn’t also suggest that true freedom leads to anarchy without someone in charge. Thus David’s decision to blow up the whole school represents a clearly nihilistic worldview in which the only solution is the final solution. Of course, he fails to do this for the most romantic of reasons, but the hopelessness of his decision remains. Are we to then read the film as a treatise against armed revolution? If so, does that mean the film thinks David should have given in like everyone else and let the bullies rule Central High? That doesn’t seem likely, which explains my confusion. The point of an allegory is to have a point, which Massacre at Central High may have, but which is the only aspect of its production left at all ambiguous.

(Then again, if you avoid the sexist assumption that the protagonist of the film has to be a male, and view Teresa as its hero--or, at the very least, its moral center--then I suppose there is some hope in the film after all. While never an overt rebel like David, she also isn't afraid to confront abuse of power when she sees it. She's the one who first tries to stop the clique from raping her two friends, and she shows zero interest in the power struggle that follows after they are overthrown. In the end, to stop the madness she proves herself willing to be a martyr, yet understands the importance of David's cause enough to spare him his reputation after his death. I'm still not sure how this works overall, but I find it infinitely more palatable.)

(Then again, if you avoid the sexist assumption that the protagonist of the film has to be a male, and view Teresa as its hero--or, at the very least, its moral center--then I suppose there is some hope in the film after all. While never an overt rebel like David, she also isn't afraid to confront abuse of power when she sees it. She's the one who first tries to stop the clique from raping her two friends, and she shows zero interest in the power struggle that follows after they are overthrown. In the end, to stop the madness she proves herself willing to be a martyr, yet understands the importance of David's cause enough to spare him his reputation after his death. I'm still not sure how this works overall, but I find it infinitely more palatable.)

That said, the film still works for me because the very elements that make it an exploitation movie allow it to avoid that trap of cheesy self-importance I mentioned above. The great thing about violence, tits, and explosions is that they go a long way from overcoming self-importance. These necessary elements humble the film, and make it seem much less pretentious than any “art” film about the same subject.

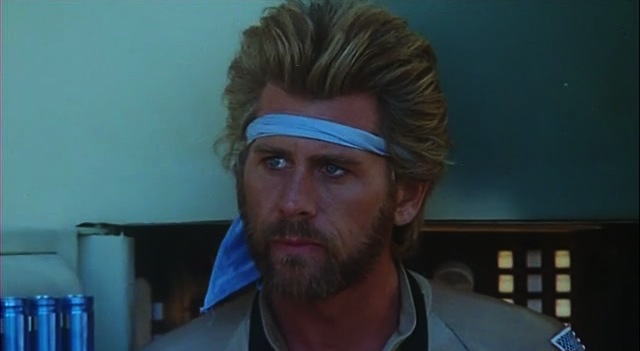

Still, Massacre at Central High is far from perfect. Its biggest flaw is the quality of the actors' performances, which range from passible (at best) to terrible (at worst). The worst offender is Andrew Stevens as Mark, which is ironic considering (apart from Robert Carradine) he would go on to have the most successful career out of anyone associated with the film (albeit mostly as a producer). Its also poorly served by a terrible music score and the strange costume decision to dress Teresa’s Kimberly Beck (who co-starred in Roller Boogie and possessed one of the most amazing bodies of the era) in outfits that look like they were directly stolen from the set of Little House On the Prairie.

Still, Massacre at Central High is far from perfect. Its biggest flaw is the quality of the actors' performances, which range from passible (at best) to terrible (at worst). The worst offender is Andrew Stevens as Mark, which is ironic considering (apart from Robert Carradine) he would go on to have the most successful career out of anyone associated with the film (albeit mostly as a producer). Its also poorly served by a terrible music score and the strange costume decision to dress Teresa’s Kimberly Beck (who co-starred in Roller Boogie and possessed one of the most amazing bodies of the era) in outfits that look like they were directly stolen from the set of Little House On the Prairie.

Despite this, though, the film works. This was proven to me during the sequence where Teresa tells David she’s going to stay in the gym and die with everyone else. I found her decision genuinely moving and there’s no way that would have happened if I hadn’t invested myself into the story. The same is true of how I felt watching David try to run on his crippled leg in order to get the bomb out of the school on time. I was invested not because I didn't want to see the school blown up, but because I wanted to see him succeed in saving the girl he loves:

And I suppose I could end this here, but there is one great big, giant, white elephant in the room that should be addressed. Namely:

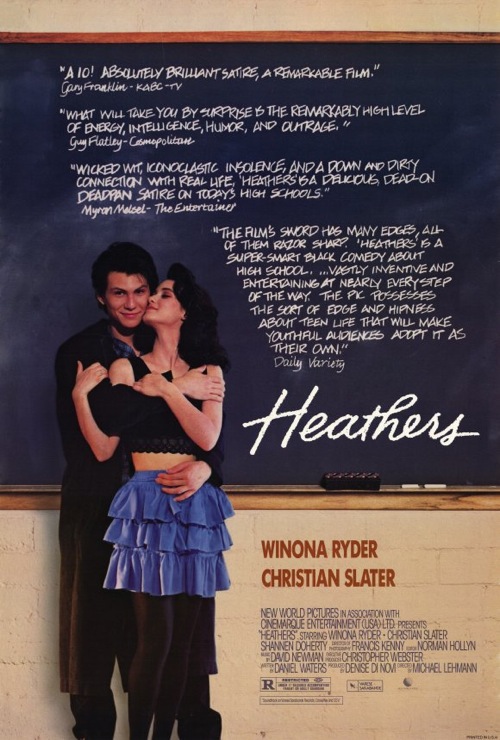

Is Heathers a remake of Massacre at Central High? No, but only because Heathers’ creators have resolutely avoided giving any credit to the older film. In terms of actual plot, they are definitely close enough to justify a lawsuit. My understanding is that Massacre is something of an orphaned production (which is why it has never gotten the DVD treatment it deserves) lost in legal limbo, which may explain why no such action has been taken. Either that or maybe some money was exchanged, but never acknowledged.

Even so, Heathers is clearly superior in its execution and overall themes. It avoids being an allegory about fascism and instead serves as one of the best satires of high school life (and society in general) ever made.

Still, a little credit given where it was due would have been nice.