B-MOVIE BULLSH*T - Part Eighteen & Nineteen "Dark(ish) Shadows"

Monday, February 6, 2012 at 6:00AM

Monday, February 6, 2012 at 6:00AM B-Movie Bullsh*t

Parts Eighteen & Nineteen

House of Dark Shadows (1970)

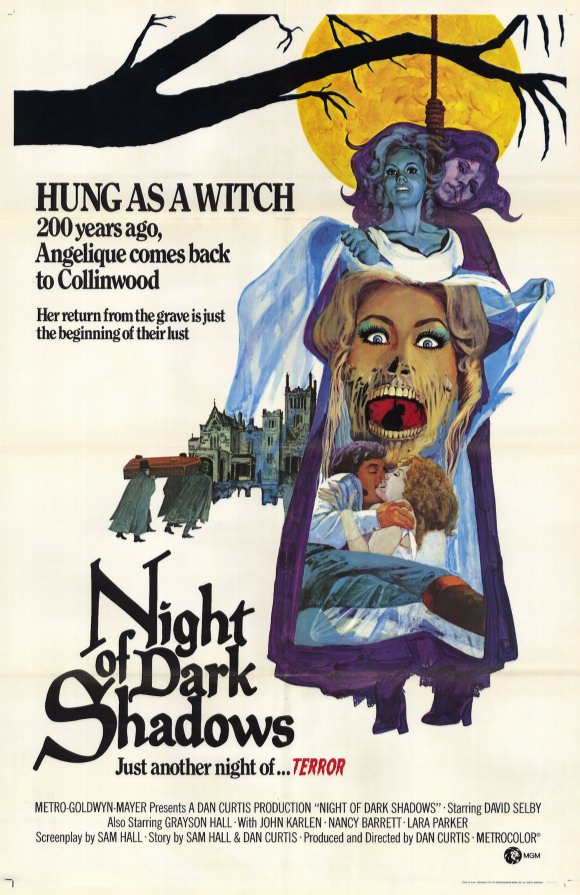

Night of Dark Shadows (1971)

Synopsis

Vampire Barnabas Collins has spent the past 200 years locked away in a coffin. It’s only when local caretaker Willie Loomis opens the casket in search of some fabled lost jewels that he is finally free to see what has happened to Collinwood, his family estate, in the centuries that marked his absence. With the exception of the main house, the estate has gone to seed, which is strange since his ancestors appear to be quite wealthy—enough so to afford a houseful of servants, including a pretty young governess named Maggie. Barnabas is shocked to discover that Maggie is a dead ringer for his beloved Josette, who committed suicide rather than join him as a member of the living dead. With the help of the Collins' live-in doctor, Julia Hoffman, Barnabas is able to hold back the effects of his vampirism through injections, but his treatment ends before he’s fully cured when Hoffman becomes jealous of his affection for Maggie. Returning to his full-on vampire ways, Barnabas spreads his affliction amongst the Collins clan, but is finally stopped from marrying Maggie and turning her into a vampire through the combined intervention of Willie and her fiancé, Jeff Clark.

Synopsis

Quentin and Tracy Collins are a young married couple who are leaving the big city to take over Collinwood, his family’s ancestral home. There they find the manor’s only two current inhabitants, housekeeper Carlotta Drake, and stable hand, Gerald Stiles. Within minutes of arriving, Quentin is taken by a painting of Angelique Collins, an ancestor through marriage who was hung for being a witch. That first night he has a dream in which he sees himself as Charles Collins, a direct ancestor who enjoyed an adulterous affair with Angelique—his brother’s wife—before she was executed. Within days Quentin finds himself blanking out and acting like Charles—including walking with his distinct limp—while vivid memories from a past life hit him at every turn. He confronts Carlotta about what is happening and learns that Angelique vowed to live on so long as her memory was kept alive by someone who loved her. It turns out Carlotta is the reincarnation of the little girl who did just that. Carlotta warns Quentin that Tracy has to leave or risks suffering from Angelique’s wrath. Quentin refuses to heed her warning and almost drowns Tracy himself while possessed by Charles. Carlotta sends Gerald to try to get rid of Tracy and her friends, the Jenkins, but he’s killed in the process. Convinced that Carlotta must be killed for them to be safe, they chase after her, only to have her fatally jump off Colinwood before they can get to her. The nightmare appears to be over, but it turns out Carlotta wasn’t the only person keeping Angelique’s memory alive. When the Collins return to retrieve Quentin’ paintings, he becomes Charles and strangles Tracy while Angelique’s ghost watches and the Jenkins are killed (off-screen) in a car crash.

The enduring popularity of the late 60s gothic TV soap opera, Dark Shadows, is one of those things I have to take on faith, since I have never seen so much as a single episode of the show, despite that fact that there are over 1200 of them in existence. According to Wikipedia, the show was syndicated to TV stations across North America throughout my childhood, but never to a single channel that ever appeared on my screen. I had never even heard of the show until I first read about it in Stephen King’s classic non-fiction look at the horror genre, Danse Macabre.

As obnoxious as it sounds, a part of me couldn’t believe that something could actually be as beloved as Dark Shadows was supposed to be, if I had never had a single opportunity to experience it. I wish I could say that this attitude of mine has changed, but that wouldn’t be the truth. If anything, having just sat through the two cinematic spin-offs the original show inspired during its run, the cult popularity of the show seems like an even bigger urban legend than it did before.

“There really are people out there who are obsessed with this?” I found myself wondering throughout the two films. But then it occurred to me that this was probably an unfair question. The better one would be, “There really were people out there who were obsessed with this?”

That I can believe. It’s easy to imagine how a production like this might have caused a cult sensation when it originally aired, over 40 years ago. Where I stumble is at the idea that this fervor still exists today, because—unlike Star Trek—all of the attempts to recreate the magic since then have met with failure—most notably a weekly prime-time TV remake made in the early 90s that died after just 12 episodes.

Many will point out the upcoming feature version directed by Tim Burton and starring Johnny Depp is proof of the show’s lasting power, but I actually think it proves the opposite. Most folks who will go to see Burton’s Dark Shadows will likely do so without any previous knowledge of the original. They will be drawn instead by the continued collaboration of one of cinema’s most successful actor-director teams. Despite interviews both will give about how much they loved the show when they were kids, the more likely truth is that the project went ahead because it was a property seemingly tailor-made to suit their mutual talents. It was either this or The Munsters (which just happens to be receiving its own “re-imagining” in an upcoming hour long dramatic pilot called Mockingbird Lane).

Many will point out the upcoming feature version directed by Tim Burton and starring Johnny Depp is proof of the show’s lasting power, but I actually think it proves the opposite. Most folks who will go to see Burton’s Dark Shadows will likely do so without any previous knowledge of the original. They will be drawn instead by the continued collaboration of one of cinema’s most successful actor-director teams. Despite interviews both will give about how much they loved the show when they were kids, the more likely truth is that the project went ahead because it was a property seemingly tailor-made to suit their mutual talents. It was either this or The Munsters (which just happens to be receiving its own “re-imagining” in an upcoming hour long dramatic pilot called Mockingbird Lane).

From what I’ve read, the two feature films the first incarnation spawned aren’t that well respected among Dark Shadows cultists—enjoying the same disreputable status as the odd numbered Star Trek films. Even though I have never seen the series I can understand why this would be true—especially in the case of the first film, House of Dark Shadows, which does just about everything wrong a film adaptation of a popular TV series can.

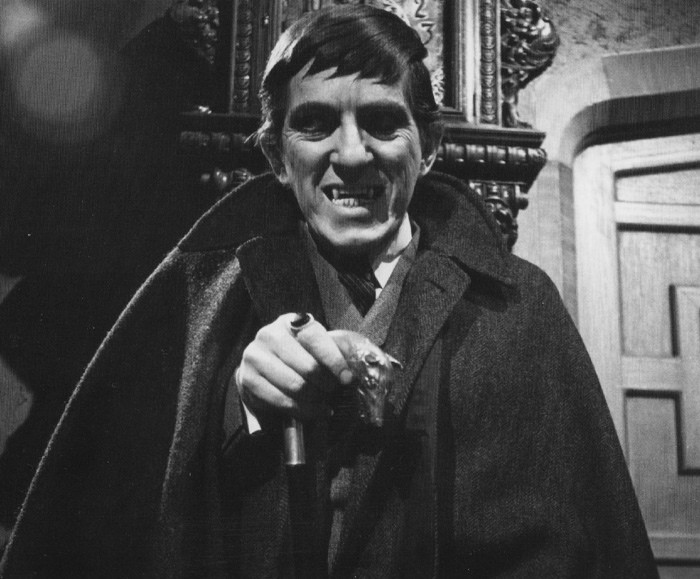

Rather than create an original story using the series’ characters that would have benefited from bigger production values (apparently the show was notoriously low budget and regularly featured atrocious special effects and sets) and more opportunities for sex and violence (the film takes some bloody advantage of the latter, but does nothing with the former), House of Dark Shadows re-visits the main storyline of its breakout character, vampire Barnabas Collins (as played by Canadian Jonathan Frid).

(Perhaps the biggest leap of faith newcomers to the Dark Shadows legend have to make is to accept the idea that Frid became a genuine sex symbol as the result of playing Barnabas, even though he makes Bela Lugosi look like George Clooney in comparison. Lacking the danger of Christopher Lee or the tragic nobility of William Marshall, Frid—at his best—most resembles Harry Dean Stanton’s less popular older brother, not a panty-wetting heartthrob in the Robert Pattison vein.)

My guess is that Frid’s popularity had less to do with his natural charisma (which is definitely not apparent in this, the first of only two movies he starred in—the second being Oliver Stone’s feature debut, Seizure) than the novelty of the character he played. When Dark Shadows originally aired it was designed as a moody, gothic soap opera without any supernatural elements. It was only six months into the series’ run that everyone figured out how fucking boring it was and decided to inject some monsters into the mix. The debut of an actual vampire in a “serious” daytime drama was a truly revolutionary concept and Frid rode a brief wave of success as a result.

My guess is that Frid’s popularity had less to do with his natural charisma (which is definitely not apparent in this, the first of only two movies he starred in—the second being Oliver Stone’s feature debut, Seizure) than the novelty of the character he played. When Dark Shadows originally aired it was designed as a moody, gothic soap opera without any supernatural elements. It was only six months into the series’ run that everyone figured out how fucking boring it was and decided to inject some monsters into the mix. The debut of an actual vampire in a “serious” daytime drama was a truly revolutionary concept and Frid rode a brief wave of success as a result.

Unfortunately vampires were old hat in the movie game and Barnabas Collins didn’t seem at all extraordinary compared to the other bloodsuckers who had filled the screen since Murnau’s Nosferatu. And this is a serious problem for House of Dark Shadows, because his is the only character who makes the slightest bit of an impression.

It’s a dilemma everyone who tackles such an adaptation must deal with—how much time should be spent developing characters at least some part of your audience is already familiar with? Spend too much and you alienate the fans of the TV show, who’ll just want you to get on with the story. Spend too little and you alienate newcomers who will spend most of the film focusing on who everyone is and how they're connected, rather than what’s going on.

House of Dark Shadows went the “too little” route and the film suffers dearly for it--a problem that is further exacerbated by the decision to compress a story that took months to unfold on television into 90 minutes of screen time. As a result, the film feels overstuffed, even though not much actually seems to be going on. The nature of soap opera is to extend drama as far as it can go—with a whole week’s worth of episodes often spent on a single afternnon in the world of the show. Because of this, the focus is set on microscopic, which means a story as slight as this one strangely feels far too big for one feature film.

House of Dark Shadows went the “too little” route and the film suffers dearly for it--a problem that is further exacerbated by the decision to compress a story that took months to unfold on television into 90 minutes of screen time. As a result, the film feels overstuffed, even though not much actually seems to be going on. The nature of soap opera is to extend drama as far as it can go—with a whole week’s worth of episodes often spent on a single afternnon in the world of the show. Because of this, the focus is set on microscopic, which means a story as slight as this one strangely feels far too big for one feature film.

This compression also explains the odd turns the characters take throughout the film. The show had weeks and even months to set up these developments, while the movie forces characters to change their behaviour without any justification from scene to scene, simply because the series' previously established plot led them organically to those points.

The best example of this is the strange journey of Dr. Hoffman (Grayson Hall, who would also play the role of Carlotta in the sequel), who goes from identifying the strange cell found in Barnabas’ victims’ blood to offering to cure him of his vampirism to falling in love with him to betraying him to being murdered by him in what seems like ten minutes worth of screen time. The entire film could have focused entirely on their relationship, but is instead treated like a necessary side-plot.

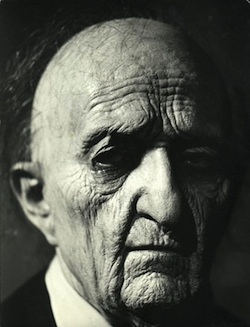

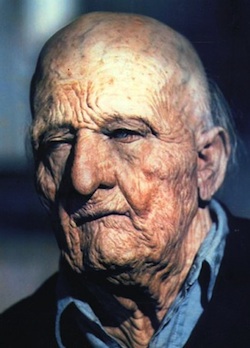

Beyond this, the Hoffman scenes also feature one moment I found interesting for its possible evidence of self-plagiarism. In the scene where Barnabas discovers that she has betrayed him, he is shown to rapidly age off screen. When we next see him he appears as an old man who bears a distinct resemblance to Dustin Hoffman’s 121 year-old character in Little Big Man, which was also made in 1970 and featured the handicraft of makeup legend Dick Smith. Did Smith make a genuine effort to differentiate the two makeup effects (and subsequently failed), or did he just do what most of us would and got lazy and handed in secondhand work? Whatever the answer, I would be curious to know which film gave him the assignment first.

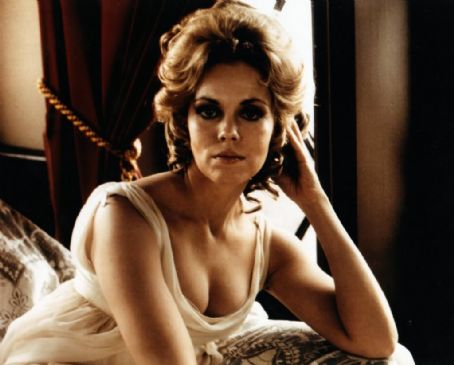

As disappointing as House of Dark Shadows was, it must have found an audience, since the sequel, Night of Dark Shadows, followed a year later. With Barnabas having been staked to death in the first film, the decision was made to focus on another villainous character from the show—Angelique Collins (as played by the gorgeous Lara Parker), the witch who turned him into a vampire when he rejected her for Josette, the true love of his life.

With a lower budget and smaller cast of characters, Night is a more satisfying and enjoyable film than House, but isn’t without its own major problems. While lacking the first film’s need to fit in all of the requisite story beats, Night instead suffers from the opposite problem—it takes too long to get to the places we know it’s going all along. Thanks to all of the constant dream sequences and flashbacks, the pacing of the first hour is extremely uneven and frequently irritating. When the final act is set in motion, the action picks up considerably, but the payoff doesn’t feel earned.

This is especially true of the ending, which feels as though it was tacked on sometime in the process to avoid a predictable happy ending. Unfortunately the end result is less chilling than it is lame, especially since it is predicated on its protagonist being a major idiot and going back to the house to pick up his worthless paintings.

Beyond Parker, Night’s major saving grace is a charming performance by a young pre-Charlie’s Angels Kate Jackson as Tracy. Whatever impact the wannabe-bleak ending does actually have is the result of the natural affection we’ve developed for her charming character.

Removed from the context of their origins, both films suffer from feeling like Americanized rip-offs of the established Hammer Studio formula, but without all of the cheesy good stuff (namely hot babes in revealing clothing) that make those films worthwhile. Viewed today its easy to see why the audience they were made for rejected them, even if the idea that such an audience actually existed still strikes me as a little hard to believe.